Signly automated signing for the profoundly deaf

Published:

Content Copyright © 2017 Bloor. All Rights Reserved.

Also posted on: Accessibility

A Question for you: what group of people born in the UK has English as their mother tongue but does not have English as their first language?

Answer: People who were born profoundly deaf. Their first language is British Sign Language (BSL), their second language is probably English, or more precisely ‘written English’.

This article explains why this is the case, what impact it has on the people of this community, and introduces new technology that is designed to help this group.

To understand why BSL is their first language we need to understand how children learn language. A baby who can hear will listen to people talking, especially their mother, and begin to make sounds and imitate the sounds they hear. They will soon realise that certain sounds relate to certain objects and actions; for example if they say ‘teddy’ their mother will give them their teddy. I am not an expert on language development but I am sure you will recognise the process I have described.

Now let us consider what happens if the baby is profoundly deaf (i.e. the child does not react at all to sounds) the process of listening to their mother and then mimicking cannot happen. However, the mother could make signs and the child could then mimic them. Starting with simple signs that we would all understand for ‘you’, ‘me’, ‘drink, ‘tired’, etc. and then going on to signs for objects such as ‘teddy’, if the mother uses the same sign every time she points at the teddy the child will start mimicking it and using it when they want the teddy. In the UK about 90% of deaf children have hearing parents. Therefore, the parents do not know BSL and many of them never become proficient. The child and parents speak different languages.

The child is now communicating and using a language, but it is not English. BSL is a complex and evolving set of signs that makes up a complete language. This is the first language for many people who are born profoundly deaf. I have used the phrase ‘profoundly deaf’ several times in this article to describe people who have no hearing to distinguish them from people with hearing impairments. Children who can hear a bit will often be able to hear enough that they can then mimic the sounds and spoken English can be their first language.

Later a hearing child will start learning to read. This, in principle, is fairly straight forward. The written word encodes the sounds of the spoken word. So the letters can be turned into a sound that is the spoken word. Likewise a spoken word can be split into its component sounds and then written down. Written English has a lot of quirks which makes this process somewhat more complex but these just make the task of learning to read and write a little more challenging for a hearing child.

The situation for a profoundly deaf child is completely different as there is no correlation between the sign for a word and how it is written, so the child just has to learn that a series of letters corresponds to a particular word and its sign or signs.

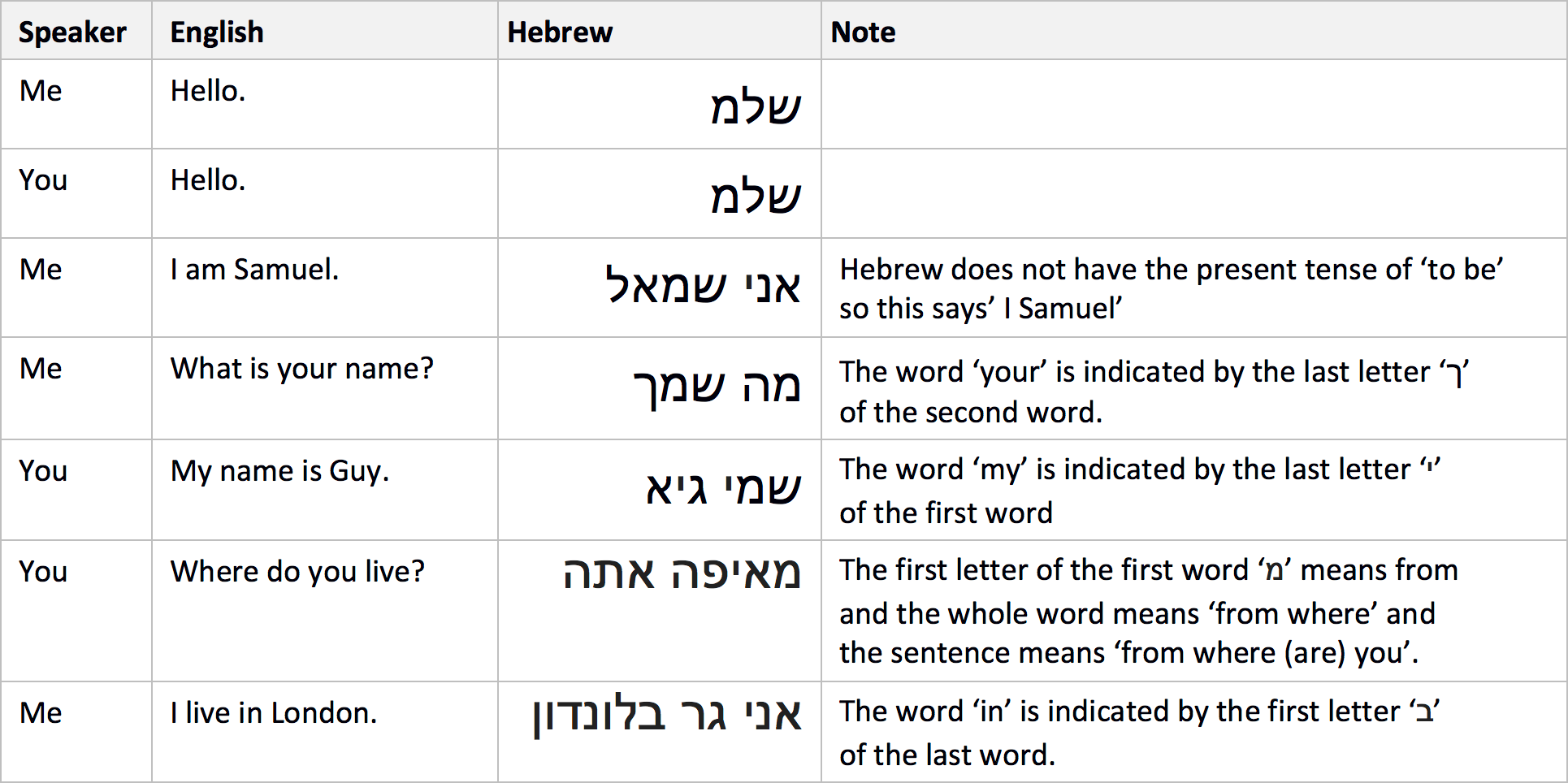

Just to give an indication of how difficult this is I want to teach you a little Hebrew. I will write the words in Hebrew characters and then give the English translation, but not tell you how it is pronounced.

Note that Hebrew has a different alphabet and is written from right to left.

This conversation will come up in the first Hebrew lesson a new immigrant to Israel will have, so it is very simple Hebrew, except it will be spoken rather than written. But you can see some of the complications: different word order, use of prefixes and suffixes, missing words and of course a series of symbols that have no bearing on the meaning of the words. I suspect that you have found it difficult to learn the 13 words and 2 names I have tried to teach you. BSL and written English have the same sorts of differences and difficulties. Now think of learning five to ten thousand words to make you a competent reader of English.

This is the challenge that profoundly deaf children face and explains why, according to some research, the average reading age when they leave school is only eight. It is obviously possible and is not dissimilar to Chinese learning their written language. Good teaching and perseverance should enable children to become proficient but it will never be as easy as their first language BSL.

A person that has BSL as their first language will find many written documents difficult to read and that means they find it difficult to be independent. It is a common misunderstanding that putting something in writing makes it accessible to Deaf people; it does not always. Most television programs now have captions and some have signing as well. Signing is the preferred option for the BSL community, whereas the captioning really helps people with hearing impairments and also people who can hear but for whom English is not their first language.

A final bit of Hebrew the word for house or home is:

![]()

So what does this conversation mean:

![]()

Answer at the end of the article.

So what could be done to make BSL speakers more independent?

Signly have created a novel technical solution. If you point this smartphone app at a poster or document that has been specially processed then a BSL signer will appear on the screen in front of the poster or document and translate the text into BSL. To see a demonstration go to https://signly.co.

The initial application is for UK Network Rail. There are several other organisations looking at implementing Signly including a bank (that will provide BSL versions of documents about opening a new account), and some museums (that will create BSL signing of information at exhibitions). The documents will have a Signly logo so users can recognise document that will be signed and then the system recognises unique information on the document (this could be a picture but it could also be some form of barcode) and delivers the signing.

In the current release every organisation will have its own app and that is certainly an easy way to get the concept off the ground. However that means the user might have dozens of different apps on their smartphone and would have to download a new app if they connected to a new organisation. In the longer term it would seem to me that there should be just one app that can interact with any organisation’s content. To make this work would require a central repository for all the content (a kind of iTunes for Signly content) and a way for the app to recognise the document and download the relevant video clip.

Signly is based in the UK so the signing is in BSL. Obviously the system could deliver other sign language such as American Sign Language (ASL) and International Sign Language (ISL).

The concept is really excellent and has been proved to wor. However, it now needs to be made commercially viable. This boils down to a method to monetise the product. My initial thought is that the app should be free and the content owners (Network Rail, the bank, the museum) should pay an amount per download and/or pay to upload and store the content.

Signly is a small start-up company driven by the desire to make BSL users more independent and not by a desire to make a fortune. It really needs a larger organisation, perhaps one with significant technological reach, to help commercialise it.

I believe the idea should and would be well used and I hope that Signly finds the road to make it viable in the long term.

Answer to the translation:

- Where are you?

- I am at home. (note the literal translation is ‘I in home’ but that needs to be turned into proper English).