GraphQL: a replacement for REST?

Published:

Content Copyright © 2018 Bloor. All Rights Reserved.

Also posted on: Accessibility

During our research on graph databases, one particular piece of open source software has come up repeatedly: GraphQL. Although GraphQL itself has a fairly modest tagline – ‘a query language for your API’ – its proponents in the graph space are making some heady claims. In particular, there are mutterings that it might serve as a replacement for REST APIs. But what is GraphQL, really? What are its benefits, and where did it come from? And can it really compete with REST? These are the questions that I’m going to attempt to answer, with varying degrees of certainty, in this blog.

GraphQL was invented at Facebook in 2012 to power its mobile News Feed. In the time since, it has come to be the primary method for data fetching within Facebook’s mobile apps. Finally, in 2015, it was released as open source at graphql.org.

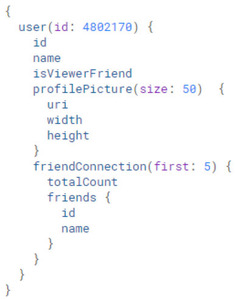

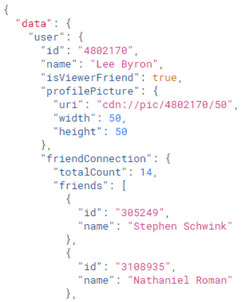

It is, as its name suggests, graph-based. Specifically, it allows you to model and expose your data in a graph structure. To illustrate, the image above shows a sample query, which will retrieve the current user, a handful of their attributes, and, more importantly, the first five users they are related to (via the ‘friend’ relationship). Note that these other users are entities and have attributes in their own right. Being able to traverse relationships like this is the hallmark of a graph. A sample of the response to this query, which is returned in JSON format, is shown below.

Notice how specific the above query and response are. Although it’s clear from context that the retrieved friends have profile pictures of their own, they are not asked for, and hence not received. This specificity dramatically reduces the possibility of both over- and under-fetching, the dual problems of receiving either more or less data than you actually wanted. The latter requires you to make additional queries, which is obviously bad for performance; the former is a subtler problem, but can still reduce performance because it requires you to process out the extra information that you’ve obtained.

In addition, unlike REST, which typically requires you to query multiple endpoints for multiple types of resource, GraphQL exposes a single endpoint for all of the information in your graph. When you consider both of these advantages together – the singular endpoint and the lack of under-fetching – you get a system that will give you the data you need in a single network request. This is a big win for network performance, particularly for mobile and tablet apps that have to deal with fickle, sluggish mobile networks.

GraphQL isn’t perfect. For example, modelling your data in a graph structure is a natural fit if you’re already storing it as a graph, as Facebook does, but much less so if you’re storing it in a table. That’s not to say GraphQL can’t be used by relational systems – it can – but it may take some additional work. However, GraphQL offers some clear advantages over REST, and in fact we have only highlighted the most significant ones here. Will it replace REST? It’s difficult to say. For all of GraphQL’s advantages, it may not be enough to overcome REST’s immense amount of market traction. In any case, it seems certain that GraphQL is going to stick around, in the graph space at the very least.