When is a Mainframe not a Mainframe? - When it is an Enterprise Server 3.0 culture, stupid…

Published:

Content Copyright © 2020 Bloor. All Rights Reserved.

Also posted on: Bloor blogs

This isn’t the first time I’ve wondered what to call the Mainframe. The term is still very much in use, according to Google, but it also carries a lot of misleading baggage for people who haven’t actually looked at a modern mainframe and its capabilities.

I don’t know if the Amazon Graviton2 project will be impacted by the possible sale of ARM to NVIDIA (if the regulators allow it), but I do wonder if it should be included in any sensible definition of what a “mainframe” is, these days. It uses custom 64-bit Arm Neoverse cores; has lots of optimisations for different workloads; and has always-on hardware-based security and encryption capabilities.

I was talking similar issues over with Chuck Lefebvre of Unisys, which has done as much as anyone to redefine what we mean by “mainframe” – culminating in a software implementation of its ClearPath mainframe which runs on x86 hardware. Unisys, like other modern Enterprise Servers, offers Choice – to run your workloads on the most appropriate platform. Its key message is that by using its ClearPath software stack, you can transition ClearPath applications to public cloud (Azure at the moment) with no expensive and risky software or data changes – which is some trick.

The question is, what distinguishes this from any scale-out x86 architecture server cluster? Well, partly it is culture. Back in the day, mainframe developers and (especially) operators saw themselves as custodians of business outcomes (although probably not in exactly those terms). They were acutely aware that the systems they built., maintained and ran were existentially important to the organisation. “Planned downtime” was discouraged (upgrading key components, both hardware and software, while a multi-CPU machine continued processing was commonplace) and less than 5 minutes downtime a year for the whole system a realistic (although non-trivial) target – the IBM z15, with Parallel Sysplex is designed to deliver up to 99.99999% availability, 3.16 seconds downtime per year on average, with some provisos. In the meantime, people supporting distributed systems in the IT silo were often quite happy with “5 nines availability except for planned downtime on Patch Tuesday” and with “prototyping in production” as long as they could fix things reasonably quickly – although business users were often somewhat less happy with all this.

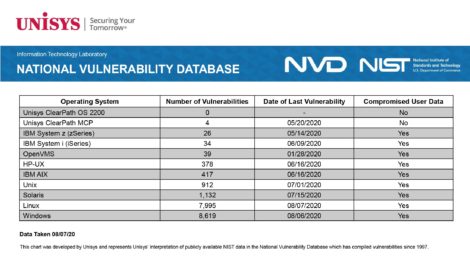

Lefebvre is still proud of the fact that Unisys ClearPath operating systems are orders of magnitude more robust and well-defined than the commodity cluster competition (see Fig 1), as are IBM z and i operating systems too, for that matter; and that reflects an attitude, and culture, some business outcomes still need.

Look at the first five OS entries on this interpretation of NIST vulnerabilities against all the rest. Installed base will have some impact, but mainframe-style operating systems are different in kind. (click to expand)

Copyright 2020 Unisys Corporation

With a nod to Unisys and its ClearPath public cloud strategy, I want to return to my original “Enterprise Server 3.0” (ES3) nomenclature for these highly stable beasts. ES1 was the original 20th Cent Mainframe (the IBM s370 running Parallel Sysplex perhaps, which is still around updated for Z); ES2 is the ubiquitous, largely scale-out, x86 cluster (using commodity hardware) and ES3 is the modern, highly flexible, scale-up and scale-out, Cloud-aware incarnation of the mainframe (exemplified by IBM System z and Unisys ClearPath, amongst others).

ES3 is defined as a range of servers actively being invested in by a vendor for (but not limited to) the general business application domain – “mainframes” excel in reliable volume computing in domains requiring integer operations (e.g., financial, indexing, comparisons, etc.), whereas “supercomputers” are designed to excel in their ability to perform floating point operations – addition, subtraction, and multiplication – with enough digits of precision to model continuous phenomena such as weather, according to the definition here. ES3 offers, in its top end machines:

- Ultimate reliability, approaching 24x7x365 (only a few seconds downtime a year, average) with no requirement for planned downtime, even to upgrade the operating system or add hardware components.

- Ultimate scalability, proven operation with billions of transactions a day, not millions; and access to more than terabytes? petabytes? of storage.

- Ultimate whole-workload throughput (rather than a focus on processing speed for a single transaction); with offloading of I/O onto separate processors or “channels”.

- Ultimate hardware-based pre-emptive multiprogramming (no process can hog a processor; it can always be kicked off with no loss of integrity or data).

- Ultimate security, with hardware-based isolation of workloads, and built-in encryption.

- The ability to run unique workloads/use cases that can’t run anywhere else – but that is hardly definitive.

ES3 vendors/systems with medium/longterm development plans for ES3 would include:

In addition:

- Group Bull GCOS is still supported by Bull, and transitioned to open systems Novascale 9000 in 2003 but there don’t seem to be any real development plans; and,

- Hitachi’s mainframe technology is still used (especially in Japan), but on IBM Z mainframes.

- NEC offers a variant of GCOS, ACOS-4 in the Japanese market place.

I asked Paul Bevan (Research Director: IT Infrastructure) to “sanity-check” this article and he says that:

Over the last 25 years, “mainframes” have increasingly moved to using industry standard x86 technology and away from designing and manufacturing their own chips (this is less so for IBM perhaps). They even started to adopt industry standard rack enclosures to house all the various components, so they even began to look like servers rather than mainframes. Still, there are some hardware features that were unique to mainframes in the way in which they used channel i/o to offload network and storage processing and leave the processors to handle the transactions.”

I think this is consistent with my identification of a need for the concept of an “ES3 box”, even today.

Paul, who has Unisys experience, also comments that Unisys had to work hard to find Intel x86 based configurations that could handle sufficiently high volumes of (particularly, he thought) storage I/O. Its partnership with Dell that saw all ClearPath Dorado and Libra mainframes delivered on Dell boxes, but I was told that this involved a lot of custom work by Unisys engineers and at the very high end it had to use proprietary i/o controllers. However, as Paul says, “it appears to have cracked this problem in the last year, as it can now deliver ClearPath as software”. Unisys tells me that it started small for this journey and scaled up over time, and finding sufficient x86 processing speed and capacity for the largest workloads was as much of an issue as I/O capacity.

Confirming that ES3 really is different, I found an interesting August 2019 article by Jim Fyffe (a solutions architect at Evolving Systems), on the issues one might meet trying to move a legacy mainframe solution to another platform. It points out that “Google receives over 63,000 searches per second on any given day. That’s 5.6 billion searches per day. Sounds impressive, doesn’t it? Now consider the fact that IBM Mainframes that run CICS handle more than 1.1 million transactions per second worldwide. That’s more than 95 billion transactions per day. If you have a mainframe the odds are high you are running CICS as your transaction manager. Your mainframe, though functionally stabilized, remains extremely important to your organization – it’s not serving up YouTube or Funny Cat videos; it’s running your business and our economy”. His key issue, by the way, is the operational challenge of freezing mainframe support while you try to implement equivalent service levels elsewhere. His company can help with such migrations but he also says that many enterprises that are initially looking to move off their mainframe: “recognize that their mainframe is hosting workloads that remain important to their business, even while their migration occurs. Some even reconsider their need to migrate off completely, effectively recommitting to the platform and taking advantage of the strengths this platform naturally offers”.

So, I think, Enterprise Server 3.0 (ES3) is a thing and there are still workloads (and reliability and security requirements) that can only be delivered on Enterprise Server 3.0. And, although IBM Z remains important in this space, it’s not the only player; Unisys, for example, is still actively developing what I call Enterprise Server 3.0.